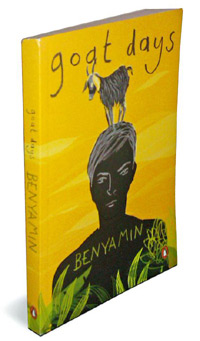

In his award-winning novel Goat Days, Malayalam literature’s young star Benyamin tells the story of a young man who, like lakhs of other Malayalis in the 1990s, goes to the Gulf. Najib is barely making a living as a sand-diver in his village when he scrapes together a visa for Saudi Arabia. At Riyadh airport, the trusting man is scooped up by an outback Saudi farmer. Thus begin Najib’s heartbreaking years as a slave at a goat farm in the desert, held by brutal masters.

Najib is an astonishing protagonist, staying convincingly humane and grateful to God even after he gets more than Job’s share. When he sees a rare visitor, a Pakistani driver, he says: “Since I had been denied normal human smells I felt that even his sweat had a scent. Out of the sheer happiness of seeing a man, I even touched him once.” There follow his attempts to get the visitor to save him, and then his startlingly compassionate explanation for why the driver couldn’t.

Despite this compelling setup, the book is unbalanced throughout by the maudlin and the repetitive. The opening chapter begins intriguingly as we wonder why Najib and his friend are trying so hard to get arrested by the Saudi police; but then it ends with annoyingly repetitive sentences echoing each other, so that the sentiment turns cloying: “Can you imagine how much suffering I must have endured to voluntarily choose imprisonment?” Or take chapter 25, where the black comedy of Najib naming his goats after acquaintances and movie stars back home is milked rather harder over several pages than the goats themselves. For the same reasons, great as Najib’s agonies are—no food, no bed, no clothes, barely any water, fear of being a nameless corpse in the desert—they are still the book’s weakest sections. The one section where Benyamin flourishes, unhindered by any need to hammer in tragedy, is the tremendous escape of the three slaves from the farm. Like prophets crossing the desert, they see amazing sights—an army of snakes, a petrified forest and dreams of ostriches.

The translation of this book must have faced a double set of troubles: interpreting both the register of rural Kerala and of rural Saudi Arabia. But can anything be more annoying than smugly concluding that a book must of course be better in the original, when you haven’t read the original? Sadly, if you read Goat Days as a book in itself and not as a translation, what you get is an arresting story in frequently dismal prose. This translation is also a reminder that sometimes readers should be left to puzzle out foreign words themselves if constant glossing slows down the story. (Benyamin’s more interesting manoeuvre with language occurs when Najib struggles to learn Arabic under the whip, and indicates that the new words he’s using may not mean what he thinks they do.)

Benyamin’s endnote reveals that the book is based on a true story he chanced upon, and “thought it would be one of the typical sob stories from the Gulf and I didn’t take it seriously”—until he met the real Najib, that is. If anything, Goat Days makes you envy Malayalam literary culture, in which you can read those ‘typical sob stories’, the stories of ordinary labourers who migrate to the Gulf—not in actual slavery but no less heart-breaking.